(Thanks for @ccerv1 and @Jonassft for reviewing + feedback.)

Public Goods Funding MUST be Evolutionary!

Tldr

- Goodhart’s Law states that when a metric is used as a target, it can no longer serve as an effective measure, leading to behavior focused on optimizing that metric at the cost of broader goals.

- Implications for DAOs and Public Goods Funding: In DAOs, especially in public goods funding mechanisms, there’s a need for systems that evolve over time, using diverse, dynamic metrics and incorporating community feedback to prevent gaming and maintain effectiveness.

- Balance Between Immutability and Evolution: While the crypto community values immutability, the post argues for a balance, suggesting that while some aspects of DAO operations should remain immutable, others should evolve to adapt to new insights and conditions - to avoid Goodharts law.

Goodhart’s Law

Goodhart’s Law is a principle in economics and statistics that states, “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

This concept was first articulated by British economist Charles Goodhart in 1975. The reasoning behind this law involves several key ideas:

- Distortion of Incentives: When a particular metric is chosen as the target for policy or performance evaluation, it often leads to a change in behavior to optimize specifically for that metric. This change in behavior can lead to unintended consequences that distort the original purpose of the measure.

- Overemphasis on Measurable Outcomes: People tend to focus on what can be easily measured and quantified. When a measure becomes a target, there is a risk that other important but less quantifiable aspects are neglected, leading to a narrower and potentially misleading evaluation of success or progress.

- Manipulation and Gaming: There is a tendency for individuals or organizations to manipulate or game the system to achieve better scores on targeted metrics, regardless of whether this results in genuine improvements in the underlying objectives. For instance, schools might focus on teaching to the test rather than improving overall educational quality if test scores become the primary measure of educational success.

- Reductionism: Goodhart’s Law highlights the dangers of reductionism in policy-making and management, where complex systems are reduced to simplistic numbers or targets. This reductionism can oversimplify reality and lead to decisions that might work well for the metric but poorly for the system as a whole.

The law serves as a caution against over-relying on any single measure or metric for decision-making, especially in complex systems where multiple factors should be considered. It underscores the importance of using a balanced set of measures and remaining vigilant about the ways that incentives can influence behavior.

Goodhart’s Law  Public Goods Funding

Public Goods Funding

In this post, I will argue that this has massive implications for how we fund public goods in the future.

Why? Public goods funding isn’t one discrete event, its a series of events over time.

What we hope will happen is this. PGF rounds create massive value creation in your ecosystem.

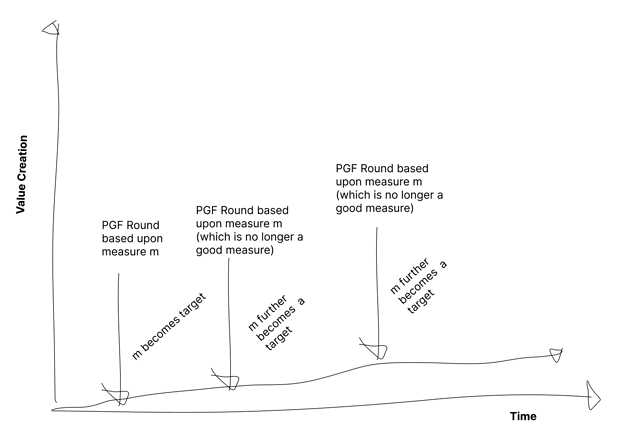

But if we take Goodhart’s law into account, what actually happens is less value creative.

In the above diagram, we see that what works in pgf_round(n) wont work in pgf_round(n+1).

As measures become targets, pgf_rounds will become less effective + thereby create diminishing returns in value creation.

This applies no matter what mechanism you use! It applies in quadratic funding contexts, badgeholder review contexts, and any other repeat public goods funding round in a adaptive complex system (like a DAO’s political economy).

So what do we do about it?

What I think follows from this is that the best PGF rounds will become infinitely evolutionary games. An evolutionary game is a game theory concept where strategies and behaviors evolve over time based on the success of previous rounds, influenced by natural selection.

As measures become targets, and targets become measures, the best systems will evolve forward in a way that is hard to be gamed + thereby does not create diminishing returns in value creation.

In the new paradigm, our experiments will look a bit like this.

Designing measure m+1

How does measure m evolve measure m +1? We have an evolutionary pressure insofar as the best ecosystems will be continuously evolving their measures forward, but in what ways can we do it?

This is the frontier, and so unless you’ve run dozens of PGF rounds, you probably don’t know the answer (yet). But we can reason about this. I think there are a couple ways we can think about it though.

- OODA Loop - Each PGF round is an OODA (Observe Orient Decide Act) loop by the mechanism designers. After each PGF round, mechanism designers will have to learn from that round, and figure out how the measure fared, and evolve it forward based on those learnings.

- Algorithmic Randomness: Introduce elements of randomness in the reward or evaluation processes to reduce predictability and the effectiveness of gaming strategies. For example, random spot checks or audits can be used to ensure compliance without the system being entirely predictable.

- In RetroPGF, the voting on metrics element of Round 4 design has a good amount of randomness built into it, as well as hard to predict game mechanisms like quorum rules and scoring formulas

- Community Feedback Mechanisms: Implement robust feedback systems that allow participants to report and address concerns about the integrity of the metrics or behaviors in the community. This feedback can be used to refine and improve the system continuously.

- Hard to game metrics - metrics that are hard, or expensive, to game, will be resistant (but not immune) to goodharts law.

- Diversified Metrics: Rather than relying on a single metric or indicator, use a diverse set of metrics to assess performance or impact. This helps ensure that different aspects of the desired outcomes are being captured and reduces the risk of any one metric becoming overly dominant.

- Dynamic and Adaptive Metrics: Implement mechanisms that allow for metrics to be adjusted or replaced as the system evolves. This adaptability can help prevent the gaming of static metrics and ensure that measures continue to align with the underlying goals of the DAO. Metrics should also have counterbalancing forces, eg, new users vs retained users. It’s very hard to do both

- Cap and Rotate Mechanisms: For critical metrics or roles within the system, consider using caps (limits on the maximum score or benefit) and rotating the focus among various metrics or areas. This can prevent over-optimization for any single metric and encourage broader contributions across different areas. An example of this policy in practice: one metric can never be more than 20% of the allocation.

A feature in my view — is that this is a competitive landscape. If lots of actors start trying to game a metric, then it’s value collapses. There will always be alpha in looking for areas where you have outsize impact in hard areas.

Immutable => Evolutionary

In much of the history of the crypto ecosystem, we have placed a value on complete immutability of our protocols.

Often, this is for good reason. Immutable protocols are incorruptible. We need this in our protocols for money - which according to crypto lore, should not be subject to the whims of any party. Because of this, we have uncensorable money, unprintable money, in BTC + ETH.

But do we need immutability in every protocol for everything?

Crypto-era Public Goods Funding has been born from this era of immutability, but it must also transcend it in order to be successful.

- We can gain the benefits of immutability in some places (eg intra-round, we should depend on credibly neutral protocols where anyone can verify the vote count), while we partially deviate from it in between rounds (for good reasons, outlined above).

- We must recognize that our emphasis on immutability has often made us aim for the perfect solution and think less iteratively. Public Goods Funding experiments could and should take the opposite approach - iterate towards a local maxima over time. Have a bias towards action + have the courage to ship something imperfect soon over never shipping the (theoretically) perfect thing.

Conclusion

Goodhart’s Law, introduced by British economist Charles Goodhart in 1975, articulates that “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.” This principle highlights how using a specific metric as a target for policy or performance can lead to behaviors aimed at optimizing that metric, often at the expense of the intended goal. This manipulation and overemphasis on measurable outcomes can distort the original purpose of the measure, reduce the complexity of systems to simplistic numbers, and potentially lead to misleading evaluations.

We think this has massive implications on the funding of public goods in decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), particularly through mechanisms like quadratic funding and badgeholder review.

We suggest that the best public goods funding (PGF) systems would benefit from being evolutionary and adaptable, incorporating strategies such as diversified metrics, dynamic adjustments, and robust community feedback to stay effective and resistant to gaming.

We advocate for a balance between immutable protocols and adaptable strategies to ensure long-term success in funding public goods.