Kudos to @umarkhaneth , @owocki and @sejalrekhan for putting this together with me!

TL;DR

- The recent Zuzalu QF rounds ran using private voting to prevent kickbacks. This is different from the first Zuzalu round, which was public.

- In this post, we analyze differences between the public (Q1) and private (MACI) Zuzalu rounds to empirically evaluate the effectiveness of this approach at preventing kickbacks. We find mixed results, indicating the difficulty of determining whether this approach was effective.

- We compare different anti-collusion strategies and how they could be combined to achieve results that best aid the community in funding the right projects.

Introduction

Last month Gitcoin spearheaded its first successful implementation of MACI (Minimal Anti-Collusion Infrastructure) in a quadratic funding round for the Zuzalu community.

MACI ensures private voting to reduce incidences of bribes or kickbacks. It makes it impossible to send or request a transaction receipt to verify that someone voted a particular way. However, vote integrity is still preserved through the use of zero-knowledge proofs and the results are still guaranteed to be correct. However, MACI is not a voting algorithm – instead, it’s a wrapper around another voting algorithm which adds extra security. In this case, MACI was a wrapper around standard Quadratic Funding.

As data science nerds (Umar) and fairness-obsessed mechanism designers (Joel), we’re constantly looking for ways to improve our mechanisms and spot new issues. However, analyzing the quality of public goods funding results is tricky because there’s no way to tell what the results “should” look like. The best we can do is analyze patterns in the data over time. Luckily, the recent MACI rounds, which focused on Zuzalu-related projects, bear a lot of similarities to the non-MACI Zuzalu rounds that happened in Q1 of this year: both sets of rounds focused on the same community, had the same subdivisions (tech and events), and we can even look at the folks who claimed a ZuPass in Q1 to get a group of users roughly comparable to to the folks on the allowlist for the MACI rounds (all of our experiments on the Q1 rounds are filtered to look at just the ZuPass holders).

So now, let’s go over some common patterns that can indicate collusion. For each pattern, we’ll first ask how we would expect the MACI data to change if it were reducing kickbacks, and then see what really happened.

Pattern Analysis

One way collusion could kick off is with a message in a private group chat. We would then expect the donations to that project from those group members to be close together in time and/or close together in donation amount.

Entropy is a measure of unpredictability or randomness. Here we apply it to donation patterns. Higher entropy would suggest more diverse, less coordinated donation behavior, while lower entropy would indicate more predictable or potentially coordinated patterns. We calculate entropy by measuring the diversity of donation amounts for each day, where a wider range of donation amounts results in higher entropy. We would expect a round with kickback-motivated donations to have lower entropy.

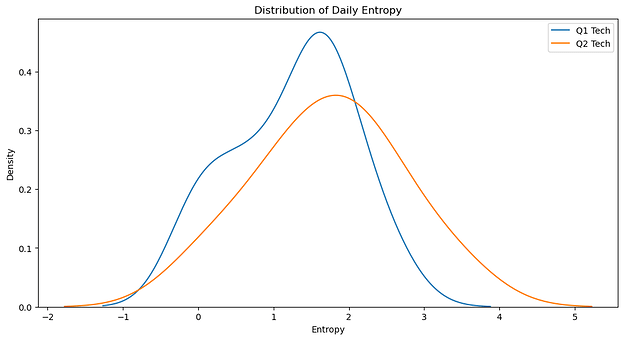

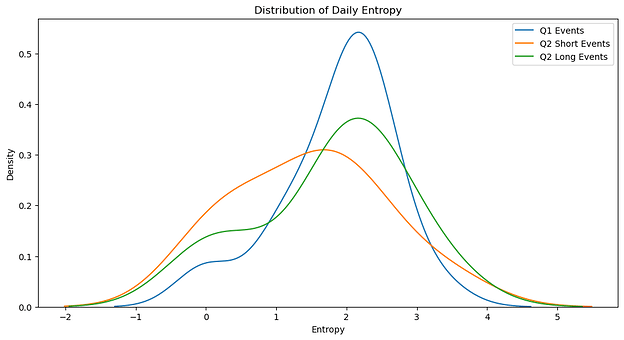

In the entropy distribution graph, the position along the x-axis indicates the level of entropy (randomness), with higher values suggesting more diverse donation patterns; additionally, curves that are taller and narrower indicate more consistent day-to-day entropy, while wider, flatter curves suggest more variability in daily donation patterns.

The Q2 Tech round showed higher average daily entropy (1.73) compared to Q1 Tech (1.25) and a slightly wider, flatter curve suggesting more variability. The increase in average entropy from Q1 to Q2, although not statistically significant, suggests MACI might have encouraged more diverse donation patterns.

In the Events Rounds, Q1 Events surprisingly showed slightly higher average daily entropy (1.87) compared to Q2 Short (1.48) and Long (1.79) Events. On the other hand, Q2 rounds displayed broader entropy distributions, indicating more day-to-day variability.

Overall, MACI’s impact varies between Tech and Events rounds. While the Tech round shows promising signs of increased donation diversity, the Events rounds had entropy values that were closer together. The results indicate that MACI’s effects might be more nuanced or harder to detect than anticipated, potentially influenced by other factors such as the nature of projects (tech vs events) and changes in the round structure.

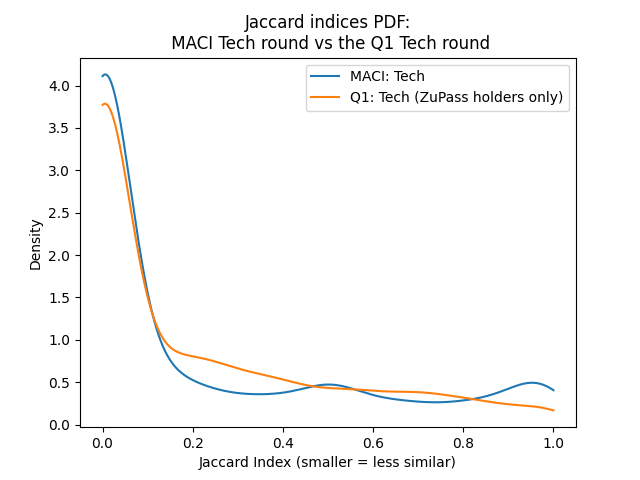

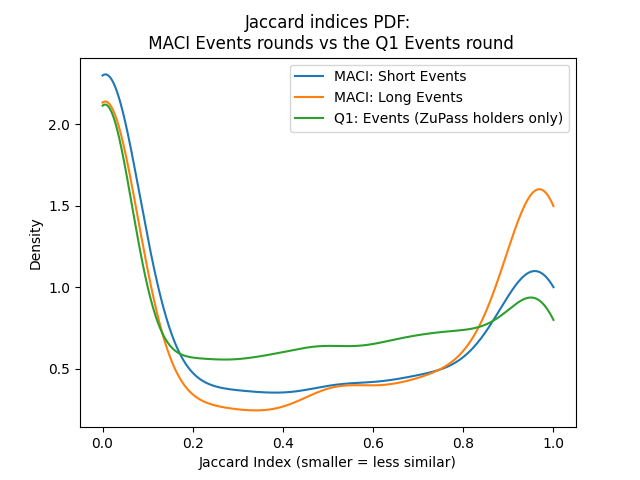

Bribery attacks often result in donation patterns where many voters donate similarly. One popular way of measuring similarity is with the Jaccard index. It’s measured like this: for two voters, first find the set of projects they both donated to. Then their jaccard index is the money they both donated to those “shared” projects, divided by the money they both donated overall. If the two people donated to completely different projects, their Jaccard index is 0. If they only donated to the same projects, their Jaccard index is 1.

So, if MACI was effective at preventing bribery attacks, one sign might be a more diverse donor base, and accordingly more pairs of voters with very low Jaccard indices (or similarly, fewer pairs of voters with very high Jaccard indices). However, the distributions of Jaccard indices over pairs of voters only partially affirm this pattern:

(By the way– the Q1 events round had ~35 projects, while the two MACI events rounds had 6 and 8 projects. With more projects, there’s naturally more room for donor diversity, so we controlled for this by slimming down the Q1 events round to its 7 most popular projects before running these experiments.)

These data show that while the MACI tech round had voters around as similar as they were in the Q1 tech round, the MACI long events round had significantly more pairs of very similar voters compared to the Q1 events round.

To be clear, a high percentage of similar voters isn’t a smoking gun indicating bribery attacks. For example, this donation pattern could be a result of the MACI projects each appealing to very distinct sets of users, which is especially likely where events are concerned. If one project wants to hold an event in Berlin and another project wants to hold an event in Boston, and so on, one might expect voters to be relatively single-issue in their support, only giving to the project holding an event where they live. This would result in some very similar Jaccard indices.

Evaluating MACI

MACI has immense potential as a mechanism for PGF. In the automated world of the blockchain, many types of attacks can be expressed purely in technical terms, and MACI eliminates them. Moreover, it’s also worth noting that there were much fewer accusations of projects promising kickbacks during and after the MACI rounds, compared to Q1. This could be partly attributed to not just MACI but a clearer social agreement on what constitutes appropriate behavior.

However, it’s also worth noting that we were not able to find any measure that strongly affirmed a reasonable hypothesis about how MACI’s collusion resistance would play out in the data. While entropy was slightly increased moving to MACI, voter similarity stayed the same or increased. Of course, comparing the Q1 ZuZalu rounds to the MACI ZuZalu rounds isn’t a perfect comparison, but there was certainly not a smoking gun showing that collusion was reduced by MACI.

One reason for this might be that collusion isn’t always expressed in purely technical terms – for example, by a smart contract that scans the blockchain for donations and awards airdrops accordingly. It can also be expressed in social terms – by a group of close friends all voting similarly. While MACI undeniably helps with technically driven collusion, it doesn’t have any guardrails to prevent social collusion.

A simple social collusion attack

Social collusion attacks are possible because social connections govern the actions people take just as much as technical rules do. Anyone who has ever passed the salt to someone they don’t like at a meal knows this – even without any technical or measurable incentive to perform an action (i.e. it’s not like you’re getting paid to pass the salt), social norms can still induce us to behave a certain way.

In the world of blockchain, social collusion attacks could look like a project owner getting a group of close friends to vote for them. Another attack bridging the social and the technical could look like a project owner bribing people to film themselves donating to their project on MACI in the last thirty minutes before voting closes – here, the attack is not technically sound, since the bribed persons could change their votes at the last minute, but if the attacker thinks that enough people won’t bother to do this, then it could still be profitable.

Plural approaches prevent Social Collusion

At Gitcoin, we’ve been using COCM (Connection Oriented Cluster Match) to address exactly the types of social collusion attacks that are in MACI’s blind spot. COCM is based on the principle of plurality, where proposals generating agreement across differences are preferred over proposals generating agreement within single sections of the population.

This approach prevents collusion because colluding parties tend to not have much internal diversity, and therefore aren’t rewarded as much. Of course, colluding parties can try to make themselves look more different by spreading out donations to other projects, but that also gives a leg up to the other projects they donate to.

COCM is one of several approaches to enhance quadratic funding’s resistance against social collusion, building upon Vitalik Buterin’s earlier work on Pairwise Matching. While both methods aim to reward diversity, they differ in their approach. Pairwise Matching calculates a similarity coefficient for each pair of donors, reducing matching for projects with highly similar donation patterns among their supporters. COCM, on the other hand, examines the relationships between projects based on their shared donors, rewarding projects that attract support from donors who contribute to diverse sets of projects. In essence, Pairwise Matching focuses on individual donor behaviors, while COCM considers project-level relationships.

The good news is that there’s no reason why MACI and either COCM or Pairwise can’t be combined. MACI isn’t a voting mechanism in and of itself – it’s more like a wrapper around a mechanism that adds extra security. Right now, standard QF is inside that wrapper, but one could theoretically put COCM or Pairwise inside instead. This has never been done before (to our knowledge) and would likely pose a significant technical challenge but should still be possible.

Impact of COCM and Pairwise

When it comes to the funding differences between QF and COCM or Pairwise, we should examine both the direction and magnitude of the potential change. To understand “direction”, we can look at whether a project’s funding would increase or decrease. To understand “magnitude”, we look at by how much.

One natural question to start with is: did COCM and Pairwise shift funding amounts in the same direction?

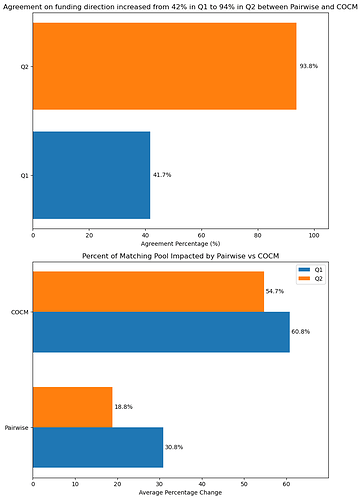

In Q2, Pairwise and COCM agreed significantly more than Q1 on the direction to shift a project’s funding (93.8% vs 41.7%). This means that if used in conjunction with MACI during Q2, either of these mechanisms would have tended to move results in the same direction. One potential cause behind the large increase is the switch to MACI: if MACI successfully reduced technically-driven collusion, then all that remains would be social collusion. This is where mechanisms like COCM and Pairwise are designed to work. In other words, Pairwise and COCM may respond differently to technical collusion (hence the larger disagreement in Q1), but similarly to social collusion (hence the smaller disagreement in Q2).

Across both Q1 and Q2, COCM tends to redistribute much more funding among projects than Pairwise (57.8% vs 24.8%). This makes sense because COCM constitutes a broader change to standard QF. It also means that for communities particularly worried about the impact of collusion, COCM is a stronger choice.

Attached here is the project-level matching allocations under each mechanism. We want to note that the exact implementation of QF used here and that the actual matching was paid under was CQF (Capital-constrained QF as defined on page 17 of this paper).

Conclusion

Quadratic funding is meant to help solve coordination failures like the tragedy of the commons, where even though everyone benefits from public goods being funded, they don’t get funded because no one individually wants to pay the price. In theory, QF incentivizes contributions by promising big subsidies for donations, therefore making it “worth it” for individuals to pay the price. In practice, however, this opens the mechanism up to collusion, which could be expressed in technical terms, but can often be expressed in socio-technical terms as well.

Using MACI as a wrapper around QF is an excellent solution for preventing technical attacks, but it can’t prevent attacks with a social component. To tackle that problem, we need to rewrite QF itself to preferentially subsidize the contributions of funders who appear less coordinated, or in other words, who support different projects from each other. This is what COCM and Pairwise do.

Each of these algorithms promotes a different winning strategy for projects. QF promotes projects to motivate their donors to support them and only them. COCM promotes projects to motivate their donors to also support other projects. QF pushes the winning strategy toward fragmentation while COCM promotes bridging.

If you have an idea for a collusion-related pattern to look for in the data, please let us know! We can’t share MACI data publicly but would love to run whatever experiments the community thinks would be useful.